Creating Value with Renewable Microgrids

As interest has grown in localized renewable generation, the discussion is shifting to what value these systems create for their owners and users. Indeed, from policy makers determining regulatory and legal frameworks, to individuals looking to invest in home energy systems, to companies trying to secure their power, the underlying value creation and economics of renewable microgrids is critical to determining appropriate applications and configurations. Renewable microgrids are now being used in many roles and applications covering sectors as diverse as the public sector, residential communities, and industrial and commercial users. Understanding the range of value of microgrids is critical to understand the cost-benefits of the system as well as make analytical comparisons with potential alternatives.

The value creation from renewable microgrids should be thought of in terms of direct value and indirect value. The direct value creation of a renewable microgrid is based on the benefits directly associated with the power generated from renewables on site.

Renewable microgrids can usually supply competitively priced power that is typically lower cost than local diesel power and often lower cost than grid alternatives (especially in locations with good renewable resource and when all grid charges and costs are included). Non-fuel based renewable generation (e.g. PV, wind, small hydro) also offers a significant advantage in price certainty versus fuel-based alternatives (e.g. diesel or natural gas) that are impacted by highly variable resource prices. This higher cost certainty makes planning and forecasting much simpler and provides economic value similarly to the difference in a fixed rate mortgage versus a variable rate mortgage.

The other direct benefits of renewable microgrids are on the additional reliability of security of supply that localized power can provide and the low emissions per unit of power. The additional reliability and power quality can be though of as an insurance against loss of power and/or damage from outages and low power quality. To capture this benefit requires storage and/or back-up generation to be included in the microgrid. The final direct benefit of renewable microgrids is the improved environmental performance and particularly the reduction in emissions for the system. In economic terms, the low emissions possible with local renewable microgrids can be evaluated based on the costs of the emissions (for CO2). Although other emissions are generally not traded, and so more difficult to value, where relevant the value of the avoided emissions can be thought of in terms of the cost of eliminating those emissions in an alternative system (e.g. the cost of scrubbers or filters that would be needed to eliminate the comparable amount of emissions).

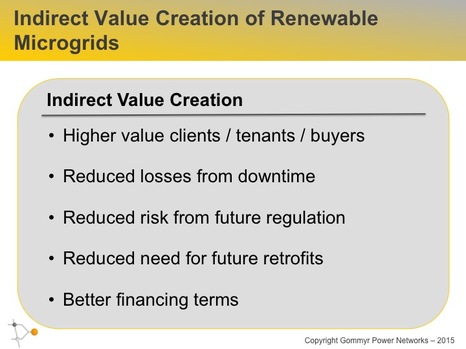

Overall the direct benefits of microgrids are generally clear, well-understood and can be measured or estimated with relative precision. However, there are several additional economic benefits that can be achieved with renewable microgrids that can be thought of as indirect benefits. These benefits are typically more application dependent, less certain and often more difficult to assess and estimate. However, they can be as, or even more, important than the direct benefits in certain cases. Some important indirect economic benefits are provided:

Overall these indirect benefits really fall into two main groups – firstly indirect benefits from being able to obtain a premium due to a more “sustainable” or “green” offering and secondly from reducing additional risks and potential future costs. There is growing evidence and examples of consumers (and increasing investors and financiers) being willing to pay more for sustainable and climate-friendly offerings. Incorporating renewable energy and energy efficiency into a local microgrid can such a low emission and more sustainable solution. The second group of indirect benefits involves risk mitigation – this covers everything from being ahead of the curve in regards to building, energy, and energy efficiency regulations, to being able to cater the power supply to secure specific loads (e.g. refrigeration for food supply). The value generated by these indirect benefits can be substantial and create further justification for implementing renewable microgrids.