Death of the PPA – Is it time for…

Long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) are a cornerstone in the business model of most renewable power generation projects. Together with fixed feed-in-tariffs (FITs), usually set at favourable above-market rates, and supported by government policy (and in many cases public money), PPAs have help propel the growth of renewable power generation around the world. Investors and banks have heavily favoured the PPA model for the additional security it is perceived to bring. For most renewable power projects, a long-term PPA is a requirement for project investment or financing. Typically, the duration of project finance will match or be shorter than the duration of the PPA. In practice however, PPAs and FITs have been less reliable and stable than expected with many countries and regulators retroactively imposing changes to tariffs, additional taxation or additional restrictions. These changes have all been used to reduce project returns. It may actually be the case that PPAs and FITs have given investors false security and encouraged less due diligence and analysis by making projected cashflows seemingly easy to predict and evaluate.

Supporting the growth of renewable energy through implicit or explicit subsidies has made sense in order to allow the sector to achieve critical mass and for technologies to mature. However, the cost of this support has been paid by power consumers and taxpayers.

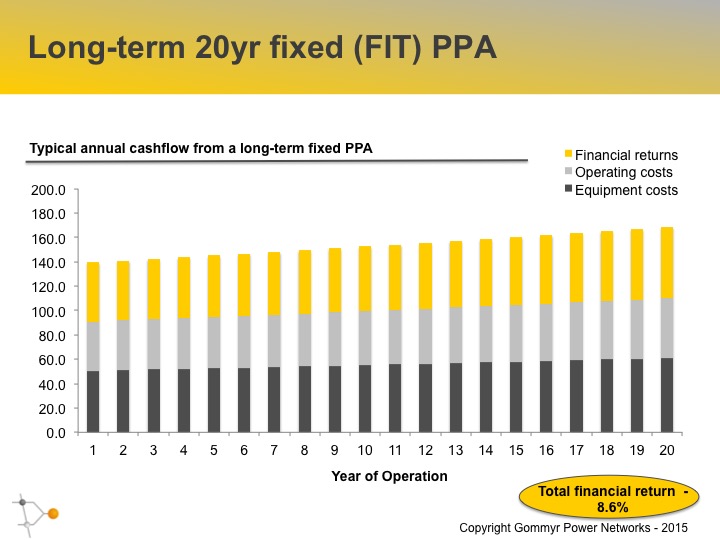

An example of the annual cashflow from a classic renewable PPA based on a fixed FIT is shown in the chart below:

Notable in the chart is that payment is consistent and slowly increasing (typically based on an agreed-upon inflation measure). However, the buyer is obligated to purchase the power under the agreed terms for the entire period (20 years in this example) and has very limited scope to change the amounts paid or cancel the contract.

Returns for traditional long-term PPA projects are currently as low as 4-5% in recent years in mature markets such as Europe and North America. These low returns where due to two factors – firstly the low interest rates environment has led investors to seek any premium over government bonds and secondly the maturing of the markets and technology has led to perceptions of photovoltaic projects as safe infrastructure investments. Indeed they have been treated as long term bonds with much of the specific project and operating risks considered minor when bundled into a portfolio of projects. Even in emerging markets, the project returns on photovoltaic projects is often less than 10% even with the associated country and currency risks.

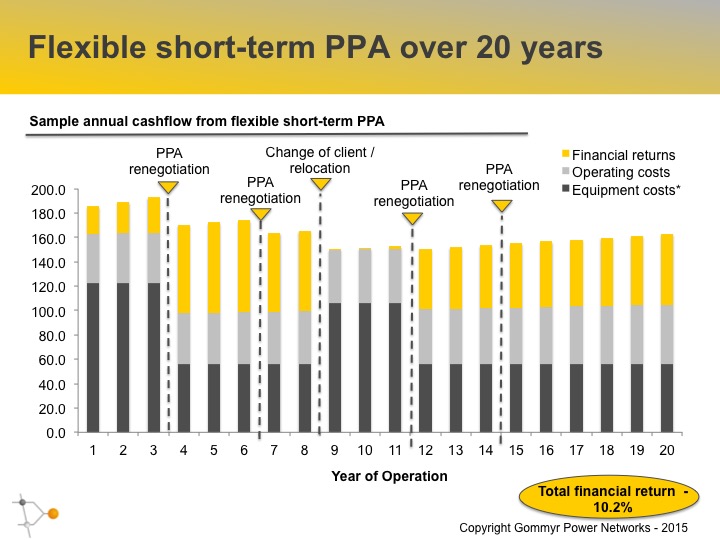

Using flexible or short-term PPA will lead to a very different project cashflow as shown in the chart below:

Notable in this example are the changes in the cashflow over the period. Although inflation adjustments are included within the short-term agreements, the cashflow is reduced at most renegotiations as the market price of power comes down due to price reductions in the equipment and from technology advances. If there is a change in client (as in year 8 of the example), the owners/investors may receive almost no return or indeed lose money to cover equipment relocation. However, this recovered in the periods of higher returns and the overall returns from the flexible PPA are higher than in the long-term case. Also notable is that the buyer/power user not only has increased flexibility but that they also benefit from future equipment improvements in the form of lower future payments. Indeed the price paid by the power purchaser is lower in the final 8 years of use with the flexible PPA than with the fixed long-term PPA.

Overall, the benefits for investors and market participants will be significant. Projects will be able to achieve higher returns over their lifetimes, many more projects will become accessible and feasible as counterparties will not be required to lock in to 20 year agreements, and the additional momentum generated will propel a virtuous circle of technology development, lower costs, more projects and higher market awareness. The higher returns from shorter term and flexible PPAs will be driven by higher initial power costs. Asset owners are providing flexibility and convenience in return for a higher upfront rate. In the example given, the generating assets are moved once during their lifetime (year 8) and interestingly, the power cost to the user is lower than under a fixed PPA for the final 8 years.

The underlying case for abandoning long-term PPAs for renewable microgrids is based on the important fact that localized renewable power is cost effective relative to conventional retail power for many markets and locations. This advantage is expected to increase further as technology improvement continues to decrease equipment and operating costs for renewable and storage and conventional power costs reflect forecast commodity price increases. This dynamic creates the opportunity for renewable asset owners and investors to offer more flexibility to power users as a catalyst to grow the renewable microgrid market in the coming years.