Maximizing owner value – structuring flexible renewable microgrid PPAs

Building on the analysis of short versus long-term PPAs in a previous post, it is critical to understand the differences in structure and terms for a flexible short-term PPA relative to conventional fixed long-term PPAs. The attractiveness of flexible and short-term PPAs are based on the current market dynamics in which the cost of locally renewable generated power can compete with conventional power, either local diesel generation or grid supplied fossil fuel generation as well as with future renewable systems.

There are of course several important limitations for a flexible PPA – the main issue being that to offer a truly flexible PPA does require that the project assets be movable for the case in which a PPA is not removed. All assets that are not movable and costs that will be incurred if the assets are moved need to be covered within the initial term of a flexible PPA. This requirement adds cost to the asset owners and may not be technically (or economically) viable for certain projects. However, for projects where a flexible PPA is feasible, it can make localized renewable generation possible for end-users who otherwise may not be able to commit or accept a standard 20 year PPA and may be preferable even to clients who could accept long term PPAs.

In general, flexible PPAs are best suited to photovoltaic and battery assets as these can be moved and reinstalled with manageable costs and have the potential to be usefully redeployed at a broad range of different project sites. However there are flexible wind, small hydro and biomass systems that meet these requirements and can also benefit from flexible PPAs.

The concept of how to structure a flexible PPA is relatively simple – the value of the long-term assets should be amortized over their useful lives and the value of short-term and non-transferrable assets and costs should be amortized over the initial duration of the PPA. The costing should also reflect the risk of periods of non-use of the long-term assets (this is dependent on the duration of the initial PPA period, the off-taker and future market conditions). In addition, the expected sale price per unit of power for a flexible PPA will go down at future price negotiations as renewable and storage technology costs continue to decrease in the future. This should not be a significant issue for most projects as the short-term costs will be covered in the initial PPA term allowing the assets to compete with new technology as long as the reduction of the long-term assets is not greater than the short-term costs.

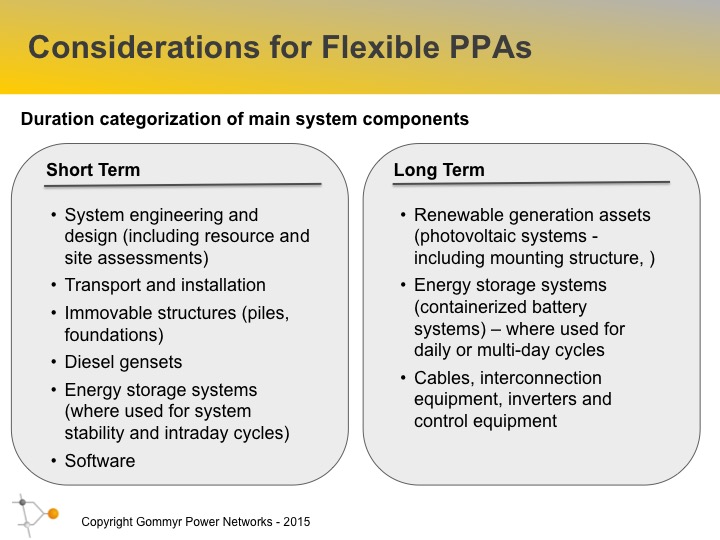

Long-term costs include the physical assets that will have value throughout their lives and beyond the initial term of a flexible PPA. These assets can be relocated at a cost that is low relative to the asset value

Short-term costs are costs that need to be covered within the initial term of the flexible PPA. A summary of the main cost components for each category is given below:

For projects with storage, one of the important issues is how to treat the batteries. The batteries for large projects can often be containerized meaning more flexibility in transporting and relocating storage. In addition, battery lifetime is closely linked to use and the number (and depth) of charging /discharging cycles meaning that the usability and state of the battery may be uncertain after the initial period. In any case, batteries typically have shorter lifespans than generating assets and relocating batteries may not make economic sense depending on where they are in their lifecycle and because energy storage costs are falling quickly (making using new batteries more cost-effective). In practice, batteries can be treated as either short-term or long-term assets depending on the project.

Overall, for both short and long-term PPAs, having a reliable off-taker and a long term relationship is critical for the success of a project. The important point with short-term PPAs is that asset owners and investors are now able to offer renewable microgrid power users more flexibility in their contractual terms. This increased convenience and flexibility comes at a certain price for the power consumers. These consumers must of course see the value in and be willing to pay for these benefits. However, the strong growth in diesel generator supplied power would suggest that there is a large need and that users are willing to pay a substantial premium for these benefits.